What are Kidney Stones?

Kidney Stones are hard deposits that form when your urine contains more crystal-forming substances — such as calcium and uric acid — than the fluid in your urine can dilute.

What are the symptoms of Kidney Stones?

Kidney Stones can cause pain, bleeding, infection, nausea/vomiting, blockage of the kidney and/or ureteral stricture, which could lead to loss of renal function.

What causes Kidney Stones?

Several risk factors may increase your risk of developing kidney stones, but they often have no definite single cause. Stones form when your urine contains more crystal-forming substances than the fluid in your urine can dilute. Your urine may also lack substances that prevent crystals from sticking together, creating a perfect situation for stones to form. Patients who develop kidney stones are at increased risk of developing stones again in the future.

How are Kidney Stones diagnosed?

To determine if a patient has kidney stones, the doctor will order one or more imaging studies. These may include:

- Abdominal x-ray

- Renal ultrasound

- CT scan

How are Kidney Stones treated?

Urologists at Boston Medical Center (BMC) specialize in all minimally invasive procedures to treat kidney stones including:

BMC also offers:

- Ultrasound guided ureteroscopy during pregnancy

- Endoscopic treatment for large bladder stones

- Stone extraction in conjunction with other procedures (i.e robotic pyeloplasty)

How to Prevent a Kidney Stone

The goal at Boston Medical Center is to make the patients’ first stone attack their last. Physicians routinely perform stone compositional analysis and offer 24hr metabolic evaluation to determine risk factors for forming stones while providing dietary and medical strategies to reduce the patients’ risk of subsequent stone formation.

Ureteroscopy and Laser Lithotripsy

Under general anesthesia, a small lighted telescope called a ureteroscope, is inserted into the urethra and guided into the ureter or kidney to the stone. A laser is then passed through the ureteroscope to break the stone into small pieces that are removed from the body. Multiple stones can be treated in one procedure. Ureteroscopy is the only minimally invasive stone surgery that can be performed in patients on blood thinners. Even with this option, it is preferable to stop anticoagulants if it is safe to do so. After this procedure, a temporary flexible drainage tube called a stent is left in place to drain the kidney. It is removed in the office at a later date under local anesthesia.

Occasionally the ureter may be too small to move the ureteroscope safely, so a ureteral stent is placed. This dilates the ureter over time. In this situation a repeat procedure will be necessary and is usually scheduled 1-2 weeks later. Most patients can return to their daily activities 7-10 days after surgery or as soon as they are comfortable.

Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL)

Shockwave lithotripsy is a non-invasive way to treat a single kidney stone. Under sedation, a gel pad is placed on the patient’s back and ultrasonic shocks are used to break the stone into small pieces so it can then be passed. The stone is targeted using either ultrasound or x-ray. Although success rates are not as high as ureteroscopy, one of the benefits is that a stent is not needed. The procedure can be performed as an outpatient. The doctor will discuss with each patient the pros/cons and risks of ureteroscopy vs. SWL to get the best outcome.

Using Shock Waves to Treat Kidney Stones

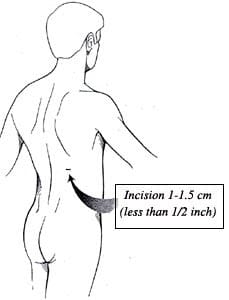

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

PCNL is the gold standard treatment option for patients with large or multiple stones (>2cm), or stones filling the entire kidney (staghorn calculus). Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is performed under general anesthesia through a small incision in the back. A lighted telescope (nephroscope) is used to see the stone. Through a sheath, ultrasound, mechanical and/or laser energy is used to break the stone into small pieces and remove them. On occasion, more than one access tract or an additional ‘second look’ procedure may be needed to remove all the stones. At the end of the procedure a ureteral stent and/or nephrostomy tube is placed to drain the kidney. Patients then spend a night in the hospital. PCNL is more invasive than either ureteroscopy or SWL and therefore carries a higher risk of complications. However for patients with large stone burdens, multiple stones, or stones resistant to other forms of treatment, the benefits of PCNL outweigh the risks.